Some microbes are old friends for humanity, helping us brew drinks, bake bread, and perhaps best of all (in my opinion, at least) break down milk proteins to help make a wide variety of yogurts, cheeses, and other dairy products. Of these, Lactobacillus acidophilus may be the most common and widely used. It’s not only instrumental in the dairy industry but is also a favoured bacteria for soy fermentation, and a common component of probiotics due to its presence in the human mouth and intestine. (And vaginas, especially those of European women. In fact, it can be an effective treatment for some forms of vaginal infection and seems to help prevent yeast infections.) Last but not least, it is used to produce sweet acidophilus milk for people suffering from lactose intolerance, performing the role that lactase fulfils in the human intestine, and there is some evidence that introduction of additional L. acidophilus into the intestine of lactose intolerant individuals may aid in lactose digestion.

So what is our versatile little buddy? Well, Lactobacillus is a genus of bacteria that metabolise sugars into lactic acid. Several strains are found in our microbiota all over the body doing just that to help break down sugary substances and prevent other, less friendly microbes from moving in by lowering the pH of the system. L. acidophilus, like its relatives, is rod-shaped and facultatively anaerobic – meaning that while it undergoes aerobic respiration in the presence of oxygen it can switch to fermentation if moved to anaerobic conditions.

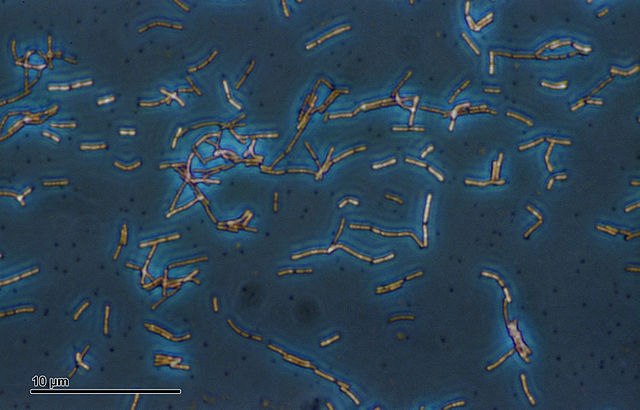

The bacterium tend to join into longer strands, several of which can clump together to form tangled colonies. This leads to the patterns that you see in Figure 1 above, with the individuals being the much shorter lines. Each individual bacterium is a bifurcated rod shape, just visible in the image.

|

| Figure 2 Close-up of a tube of L. acidophilus in the lab Source: original |

At the macro level L. acidophilus mostly looks like an average white microbe colony, as seen in Figure 2. In fact, it’s hard to make it out from the milky media it was stored in. You can just see little lumps of bacteria on the sides of the tube.

A variety of laboratory strains of L. acidophilus exist, mostly extracted from humans and chickens. It’s happiest in acidic conditions (around pH 5.0 or lower) and has an optimal growth temperature of 37°C, like most gut bacteria. There are several commercial media designed to be selective for Lactobacillus species, such as MRS broth, or it can be grown in Tomato Juice-Yeast Extract-Milk Medium. This seeks to emulate the chemical environment found in the dairy products L. acidophilus is used in, and while it is not strictly selective for Lactobacillus it has a comfortably low pH and is chock-full of milk sugars for them to digest.

Thank you for your articles that you have shared with us. Hopefully you can give the article a good benefit to us. Lactobacillus Acidophilus

ReplyDelete